CRAIG SEMON, Telegram & Gazette

STURBRIDGE (AP) — Since the publication of Bram Stoker’s “Dracula” in 1897, vampires (aka mystical beings that subsist by feeding on the life essence of living creatures) have been part of our popular culture.

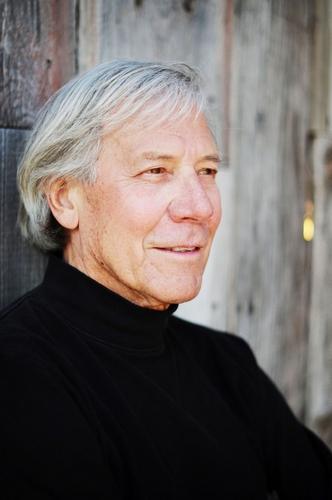

Michael E. Bell, author of “Food for the Dead: On the New England’s Vampire,” says he has unearthed unholy evidence that a form of “vampirism” existed in New England as far back as 1784 and was killing people at an alarming rate.

Bell — who plans to give a lecture titled “In the Vampire’s Grasp: Narrating America’s Restless Dead” at Old Sturbridge Village — said the culprit wasn’t your typical Transylvanian or Bela Lugosi-variety blood sucker.

“The vampires that I’ve dealt with in New England, it was really a microbe. It was the tuberculosis germ,” Bell said on the phone from his Rhode Island home. “Literally, it sucked the blood out of them as their lungs rotted because of the disease. So, people didn’t understand what was going on. They had a sense that it must be contagious because someone in their family would get sick and they would see them waste away. And they might come in the morning to see it progress and they have coughed up blood. So there would be blood on the corners of their mouths, blood on their bedclothes. And the reaction was, well, something’s obviously sucking the life blood out of our relatives.”

Even more horrifying than consumption was the Eastern European “folk remedy” New Englanders used to combat this lethal disease, Bell said.

“The remedy was to go out into the cemetery, exhume the body of the people in your family who have died already of this mysterious disease, examine the corpses, see which one might have liquid blood in one of their organs,” Bell said. “The liquid blood was interpreted as fresh blood. So the question would be how did this flesh blood get into this supposedly dead body? It must be taking the blood from the living people in the family. So the folk remedy was to exorcise that particular organ and burn it to ashes.”

It didn’t stop at burning the diseased organs to ashes.

“Sometimes, the stipulation would be that the members of the family should eat the ashes,” Bell continued. “Other variants were just burn the entire corpse. And sometimes the stipulation would be to have the ill family members stand around and inhale the smoke or stand in the smoke and kind of fumigate themselves with it. Or even a more simple remedy was just turning the corpse faced down and rebury it.”

In New England, Bell said the earliest case of vampirism he discovered was 1784 in Wilmington, Connecticut, and the most recent case was in 1892 in Exeter, Rhode Island.

“The story attached to the New England examples really don’t go into details like the corpse actually leaving the grave or biting parts of the body and sucking the blood out,” Bell said. “It’s more a folk medical practice. Here is the way you deal with consumption. But, it is what’s called vampirism, basically. And I can understand how consumption and vampires might be put together in some people’s minds because of the symptoms of consumption.”

In fact, it was the Exeter story that sparked Bell’s curiosity in the first place. A man he interviewed in the early ’80s told him the tale of Mercy Brown, whose body was exhumed, then her heart was cut out and burned to ashes.

“As a folklorist, I was very interested if this family story was just a legend or was it based on an actual event,” Bell said. “So I started doing research and I did find newspaper accounts from eyewitnesses describing Mercy Brown’s exhumation and her brother’s subsequent death by consumption. They were trying to save his life.”

One of the most fascinating stories Bell said he found involved the Congregational minister of Belchertown in 1788 having the bodies of his mother-in-law and daughter exhumed because another daughter was dying from consumption.

“You would think that this would be something that would be frowned upon by the clergy, by the religious institution,” Bell said. “And he (the minister) wrote a letter to a good friend of his and said, ‘We wonder if it was possible for the dead to be preying on the living?’ And, in the letter, he describes holding a council with family members and other leaders in the community and asking them, ‘Is it really possible?'”

In 1796 in Cumberland, Rhode Island, the town council gave a man permission to exhume the body of his daughter to “try an experiment to save the life of his living daughter,” who was dying of consumption, Bell said.

“Well, it didn’t say what kind of experiment it was but I can fill in the blank there,” Bell said. “But, once again, I think that’s an interesting, fascinating case because it shows an official sanctioning of that ritual.”

By the time Bell published “Food for the Dead” in 2001, the author found about 20 cases. Now, he said he’s approaching 100. In his research, Bell found the practice of this macabre “last-resort folk remedy when nothing else worked” was a lot more prevalent than people or, initially, the author realized.

“In the beginning, I had the feeling that this was like New England’s dirty little secret. But there’s nothing that little about it and it wasn’t secret,” Bell said. “There was a case in Vermont where the whole town turned out, something like 500 to a thousand people, to watch this woman’s heart be burned on the blacksmith scourge in the town square. When you have Congregational ministers and you have town council approving it and you have the whole town coming out to witness the event, then it’s not like it was being done out of sight and out of mind. It wasn’t being kept so secret so much.”