by Steve Williams, a Westfield resident on assignment in Alaska and contributing to The Westfield News

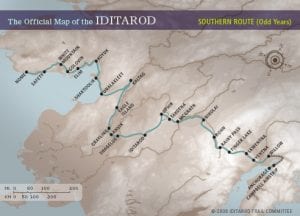

Seen here is the Iditarod trail that all 52 mushing team will follow during the 2019 race. The trail is marked with thousands of trail markers to help teams along the way.

ANCHORAGE, AK – The snowcapped Chugach Mountains loom below the clouds in the east and the the frozen, slushy water of the Knik Arm trickles slowly to the west. As I make the journey from the airport into downtown Anchorage, the sheer beauty of the land has me grabbing my jaw off the cab floor. These aren’t the Berkshires or the White Mountains so prominently known in New England. These are “real” mountains. The kind that people tell stories about climbing. The kind that take your breath away when you reach the top and peer down at the valley below. These are the type of mountains you write home about. This is Alaska. Well, sort of.

The real story of Alaska can’t be told from the sprawling city limits of Anchorage. One has to venture out much further to see the real Alaska. The real Alaska is told from the bush. The Native Alaskan Villages. The real story of Alaska is told through “The Last Great Race on Earth”, The Iditarod.

On Sunday March 3rd, 52 dog sled teams from around the world will embark on a 1,000-mile journey from Willow to Nome. Mushers and sled dogs will travel through some of the most pristine and brutal stretches of land known to man. Through jagged mountains, wind-swept tundra, and over frozen rivers and lakes, danger lurks around every corner. Sled dogs as well as their musher need to be prepared for anything. Each sled will be led by a team of 14 energetic, and ready to run huskies followed by a sled of supplies and their musher.

Iditarod hopeful winner Aliy Zirkle and her team of 16 dogs are seen traveling through the woods in Willow, AK as she leaves the race start during the 2018 race. (Photo by Steve Williams)

The race will follow it’s “southern route” again, just as it did last year. Iditarod Race Director, Mark Nordman noted there’s “lots of snow” on most stretches of the 1,000-mile trail to Nome. Up to six or seven feet in some areas. Deep, soft snow can slow a team down and this same route proved difficult for mushers last year as the winner finished with a time of 9 days and 12 hours. The longest first place finish since 2009.

Teams will make their way from the tailgate party on Willow Lake Sunday to the deep snow surrounding the checkpoint of Finger Lake. From there mushers and their teams will make the ascent across the Alaska Range gunning for the highest checkpoint on the trail, Rainy Pass. Overflow and open water due to milder temperatures during the winter months lead to potentially hazardous conditions along the trail. Nordman noted trail breakers have been working tirelessly over the last few days building bridges out of snow, trees, and brush to help alleviate the harsh conditions.

From Rainy Pass, teams will push forward to the interior Alaska Native checkpoints of Nikolai, Takotna, Iditarod, and Shageluk. It is here where temperatures become brutally cold, often dipping below -30 degrees Fahrenheit. Next is the trek across the frozen Yukon River to the checkpoints of Anvik, Grayling, Eagle Island, and Kaltag. The windiest stretches of trail from Unalakleet to Elim often carry blizzard like conditions and can derail teams as the vision of the dogs and mushers is obscured by the conditions. The final stretch awaits as teams are just 100 miles from Nome through the checkpoints of White Mountain and Safety. As they cross the ice on the Bering Sea and make their way to Front Street in Nome a sense of accomplishment and joy begins to set in. Fans, media, family and friends await at the finish line to congratulate them on their great accomplishment.

The Iditarod is rich with history. In 1925 numerous dog sled teams traveled to Nome in order to deliver medication in the midst of a diphtheria outbreak that threatened to wipe out the entire community. As a tribute to that quest and as a way to keep the tradition of dog mushing alive Joe Redington Sr. started the first Iditarod race in 1973. Dog mushing has long been an essential mode of transportation in Alaskan winters where harsh conditions prohibit other forms of travel. But dog mushing in Alaska has become so much more than just a means for travel. At its core, The Iditarod is about a human relationship with a team of dogs all working towards one common goal, to complete a 1,000 mile trek across the toughest terrain in the world and cross that finish line in Nome.

This year’s field features five Iditarod Champions in Lance Mackey (4), Jeff King (4), Martin Buser (4), Mitch Seavey (3), and last year’s champion Joar Leifseth Ulsom (1), as well as Iditarod Champion hopefuls Aaron Burmeister, Richie Diehl, Jesse Holmes, Pete Kaiser, Nic Petit, and fan favorite Aliy Zirkle. Perhaps a dark horse will rise to the top and claim their stake as champion. Maybe one of the ten rookie mushers will make a push for the top as Jesse Holmes did last year finishing 7th. Time will tell, but if the Iditarod has taught its fans anything, it is to expect the unexpected.