LISA WANGSNESS

The Boston Globe

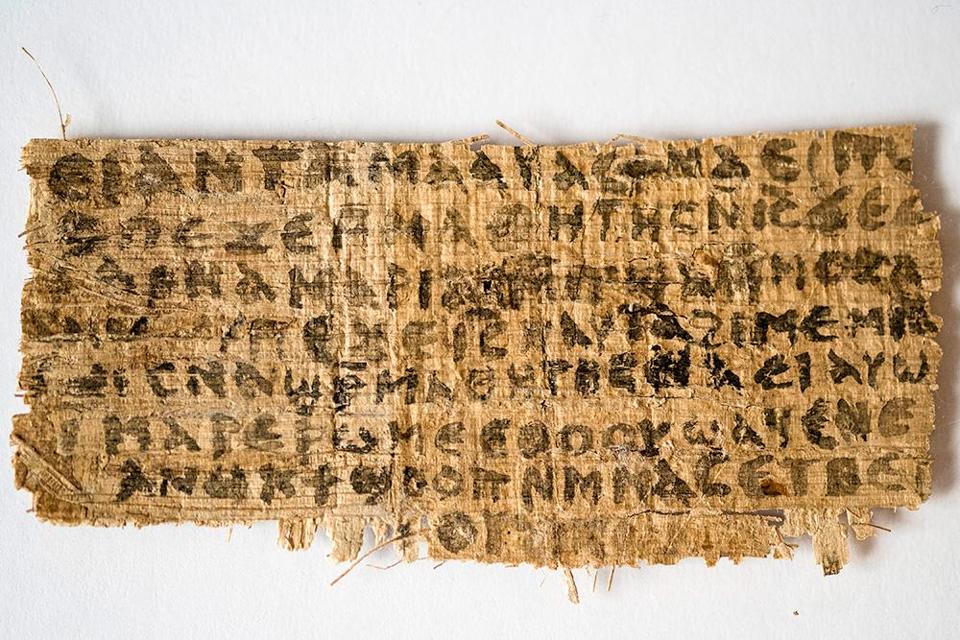

CAMBRIDGE, Mass. (AP) — Three years ago, Harvard University professor Karen L. King showed the world a tiny fragment of ancient Egyptian papyrus whose eight partial lines of Coptic script included one sensational half-sentence: “Jesus said to them, ‘My wife . . .’ ”

It was big news. The Boston Globe and The New York Times ran front-page reports; the story went global as TV crews and bloggers and wire services joined the fray.

Doubt swiftly set in.

As critical takedowns of the fragment — which King provocatively named “The Gospel of Jesus’s Wife” — ricocheted across the Internet, a growing chorus of academics cast the papyrus as a fake.

“When is this papyrological pantomime, this Keystone Coptic, this academic farce, this philological burlesque finally going to stop?” Egyptologist Leo Depuydt of Brown University wrote in an email last year.

Earlier this month, a Coptic papyrologist from Australia visited Harvard to have another look at the papyrus.

Yet his will not be the last word on what may be, centimeter for centimeter, the most controversial scrap of ancient paper ever seen. The case remains one of the most high-profile and confounding academic mysteries in recent memory.

‘It’s just a matter of evidence piling up until you finally have to say, “This does not look right.” ‘

Tony Burke, who teaches biblical studies at York University

As the Hollis Professor of Divinity at Harvard Divinity School, King holds the oldest endowed academic chair in the country. The daughter of a pharmacist from small-town Montana, she has built her career on sober and painstaking research, mainly concerning early Christian and heretical texts.

When a stranger sent her an email in 2010 claiming to have a papyrus that mentioned a married Jesus, she paid it little mind. But when he contacted her again, she took a closer look.

The owner, who asked King to keep his identity secret, brought the fragment to Harvard. King took it to New York, where she spent hours analyzing it with two eminent scholars — AnneMarie Luijendijk, a papyrologist from Princeton University, and Roger Bagnall, who directs the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World at New York University.

The handwriting was crude, nothing like a typical ancient literary manuscript. Bagnall thought it might be the work of an unskilled scribe with a bad pen. But both he and Luijendijk agreed it appeared to be ancient.

With that advice in mind, King eventually argued that the Coptic fragment was probably genuine — a fourth-century copy of a Greek composition from the second century, she hypothesized.

King never thought the fragment was evidence that Jesus actually had a wife. But she believed it showed that some early Christians portrayed him as married as they debated celibacy and the role of women in the church, specifically wives and mothers.

She was fascinated. So was everyone else. The Smithsonian Channel filmed a documentary in advance of her announcement about the papyrus in Rome.

Some scholars reacted with immediate skepticism, even scorn. Rapid-fire online exchanges erupted in the weeks following King’s announcement, as academic bloggers pored over images of the fragment. The handwriting looked strange, they said. The grammar seemed way off. And to many critics, the text bore an uncanny similarity to the Gospel of Thomas; the only surviving full copy of Thomas was hidden in Egypt and rediscovered in 1945. British scholar Francis Watson argued it was an inelegant pastiche of that gospel.

The Smithsonian Channel postponed its documentary. The Harvard Theological Review said it would wait to publish King’s paper until the fragment had undergone scientific testing.

A year and a half later, the tests were back, and the documentary and research paper were back on track. Carbon-14 tests that King had commissioned estimated the papyrus was made around the eighth century — long after King had thought, but not in the modern period.

Ink studies turned up no modern contaminants. The tests, however, could not say when the papyrus was inscribed. Conceivably, a modern forger could have bought a piece of ancient papyrus and written the text recently.

Yet expert examination of the ink’s placement on the papyrus found no obvious signs of forgery. Malcolm Choat, a Coptic papyrologist from Macquarie University in Sydney, traveled to Cambridge in late 2012 to study the fragment. He left uncertain.

“I have not found a smoking gun that indicates beyond doubt that the text was not written in antiquity, but nor can such an examination prove that it is genuine,” he wrote in a report published with King’s paper in 2014. “I do, however, believe the present case is less straightforward than some proponents of forgery have assumed.”

Doubters were not persuaded.

Beyond the crude appearance and sensational married-Jesus theme — which some thought seemed too well-suited to the “Da Vinci Code” era — many argued that the message on the papyrus must have been written in modern times.

In October 2012, Andrew Bernhard, an independent scholar from Oregon, had offered a theory that quickly gained traction in the forgery camp: Someone with a rudimentary grasp of Coptic must have cobbled together the text from a line-by-line translation of the Gospel of Thomas by Michael Grondin, published online in 2002.

Bernhard posited that the forger, using as a guide the English translation that appeared beneath each line of Coptic in Grondin’s edition, spliced together Coptic words and phrases much as a kidnapper might paste together a ransom note from newspaper headlines, then inscribed it on the papyrus using homemade ink.

This theory, Bernhard contended, would explain the fragment’s grammatical errors and oddities. It looked like the hapless forger had even copied a typo from the Internet translation.

“It was a clear cut-and-paste job,” he said.

King did not buy it. In her 2014 Harvard Theological Review paper, she noted that the vocabulary in the text was unremarkable. The most notable terms — “my wife” and “swell up” — were not in Thomas at all. In any case, she said, dependence on other, earlier texts is common in ancient literature. She found in ancient texts other examples of some of the errors and idiosyncrasies that Bernhard considered telltale links to the online Thomas.

Days after King announced the results of the scientific tests, though, a second major forgery argument emerged. It centered on a different papyrus fragment belonging to the same anonymous owner, who told King he had bought the Wife fragment along with five other Coptic papyri from a German man in 1999.

This second fragment bore text from the Gospel of John, one of the gospels in the Bible. Assuming it was authentic, King had the John fragment scientifically tested, too, as a kind of control.

Christian Askeland, now a professor at Indiana Wesleyan University, an evangelical Christian institution in Marion, Indiana, saw a photo of the John fragment in the online edition of King’s report days after she released it. He couldn’t believe his eyes.

Askeland, who had done his doctoral work on the Gospel of John, immediately saw that the John fragment was written in the Lycopolitan dialect. This made no sense. Scholars believe Lycopolitan died out long before the carbon-14 tests estimated the papyrus was manufactured.

The writing on the fragment seemed to precisely mirror every other line of a Coptic copy of John known as the Qau Codex. Askeland said it took him all of a minute to see the similarities.

“It was that obvious,” he said.

Copies of the same ancient text tend to look very different from one another because of variations in handwriting, paper size, and errors. But every line of King’s fragment began in exactly the same place as every other line of the Qau Codex — which was discovered in Egypt in 1923 and first published a year later. Such precise mimicry is virtually unheard-of in ancient gospel manuscripts.

More importantly: To Askeland, the handwriting on the John and the Wife fragments looked the same. If one was a fake, both were.

“My first assessment is that this a major blow to those arguing for the authenticity of GJW,” he wrote on his blog, Evangelical Textual Criticism. The blogosphere in the field went wild, and within days his photograph ran in The New York Times alongside news of his discovery.

“I didn’t think the blog post would take off the way it did,” he said.

For many scholars who had been withholding judgment, Askeland’s insight tipped the balance in favor of forgery.

“It’s just a matter of evidence piling up until you finally have to say, ‘This does not look right,’ ” said Tony Burke, who teaches biblical studies at York University in Toronto.

The discussions about the Wife fragment were largely carried out in furious back-and-forths on rarefied academic blogs, such as the NT Blog of Duke University New Testament scholar Mark Goodacre. Arguments that might have taken months or years to unfold were happening in days, even hours, as scholars who lived oceans apart shared information and argued about Coptic grammar and paleographical features.

“I think it’s fantastic, really, that so many people have weighed in, and we’ve actually come to a fairly strong consensus reading of the piece in a fairly short period of time,” Goodacre said. “I do think this is a case where the Internet and blogging has really helped scholarship.”

At times, though, the tone became fraught. Askeland named the original blog post about his discovery “Jesus had an Ugly Sister-in-Law,” setting off a controversy that cascaded into a debate about whether gender and ideology had played a role on either side of the discussion.

In any case, the prominent journal New Testament Studies prosecuted the case against the Wife fragment in its July 2015 issue, publishing a series of articles that powerfully argued for forgery, concluding with a call for Harvard to retract its claims and for King to reveal the owner.

“Forgeries corrupt — and are intended to corrupt — the scholarly work of those who may be deceived by them,” the editorial said, “and they need to be exposed as conclusively as possible.”

King by that time had moved on to other academic work. But it seemed to her that critics had constructed a case against the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife without giving fair consideration to the other side — or to the vast gaps in knowledge and evidence that make certainty so elusive.

Were the Wife fragment and the suspicious John fragment really written by the same person? No expert papyrologist had done a firsthand analysis of whether the handwriting was the same, King pointed out. In fact, she said, no one making arguments for forgery had examined the actual papyri.

She noted that James Yardley, an electrical engineer at Columbia University who analyzed the ink, determined the inks on the two fragments were similar, but not identical. His research team was now developing a new method of estimating the date of ancient ink and planned to apply it to the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife.

“I’m open that, in the end, it might be a modern production,” King said in an August interview. “But right now, the important thing is process.”

The Gospel of Jesus’s Wife, she added, had undergone more scientific testing than any other papyrus fragment of its size. Would other, more everyday papyrus fragments whose authenticity is taken for granted hold up under such scrutiny?

Days after that interview, King released an English translation of the fragment given to her by the owner in 2011. She had done her own translation; the owner’s seemed wrong, so she put it aside. At the Globe’s request, she posted the one the owner gave her on the divinity school’s website.

Bernhard seized on it and, working feverishly through the night, drafted an analysis showing that the owner’s translation used the same English words Grondin had, repeating Grondin’s mistakes and twice translating Coptic words that appeared in the Gospel of Thomas, but not on the fragment.

Goodacre, who posted Bernhard’s analysis on his blog, called it “absolutely flabbergasting.”

This month, Choat, the Australian papyrologist, returned to Cambridge to study the Harvard papyri on his way to a conference in Atlanta.

He spent more than eight hours inspecting the papyri at the Houghton Library, supervised by a member of the library’s staff.

In one spot on the John fragment, Choat detected ink where it shouldn’t be. In another area, ink was absent where it should have been present.

Wrong dialect, line breaks that exactly replicated another manuscript, and now, misplaced ink: To Choat, the most logical explanation was forgery.

Choat compared the handwriting on the Wife and John fragment.

“They look similar, very similar, in the way the letters were formed,” he said afterward.

“It’s the most economical hypothesis that they were written by the same person.”

Choat said his verdict is not final: Yardley’s team at Columbia hopes to publish the results of its ink study in coming months.

If the findings suggest that the Wife fragment’s ink is ancient — and one online report suggested the team’s early results indicate it might — the study could conceivably reignite the debate about authenticity.

Yardley declined to discuss the results before publication.

“What I have learned is that no matter what you say, it can be misinterpreted,” he said. “So the less I say, the better.”

For now, it is hard to find anyone who will defend the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife as authentic.

The discussion has shifted to the other major point of intrigue: Where exactly did the Gospel of Jesus’s Wife come from? If it is a forgery, who is behind it?

Collectors of ancient artifacts often insist upon anonymity, and it is not uncommon for researchers to grant it. King has said the owner of the Wife fragment didn’t want to be hassled by would-be buyers. According to documents he showed her, he bought the fragment from a German businessman, Hans-Ulrich Laukamp, who died in 2002.

A report on the website LiveScience has raised doubts about that story; two of Laukamp’s associates told the website he had no interest in collecting antiquities.

A growing contingent of scholars say Harvard should release copies of three documents related to the papyri’s provenance that the owner gave to King — a bill of sale from Laukamp, with a note saying he got them in Potsdam in 1963, and papers suggesting that two Egyptologists saw the fragments in Berlin in 1982.

Caroline Schroeder, a scholar of early Christianity at the University of the Pacific in Stockton, California, said she was not sure what arrangements Harvard had made with the owner.

“I think it’s Harvard’s responsibility as the institution that really promoted this piece to release everything they legally can,” she said.

King, who in her 2014 paper quoted the text of the documents almost in their entirety, said Harvard only has copies of the documents, not originals, so they are “not good data” to release.

“The copies won’t actually be useful; it needs to be the original,” she said.

She also said she plans to keep her promise to the owner to protect his identity.

“Here is my experience with the owner,” she said. “When asked, the owner supplied the actual papyri. He has said yes to every request made for testing and examination. He has agreed to store these for further analysis at Harvard . . . for a 10-year period. That is what I can verify about the owner.”

In private conversations, speculation is raging: If this is a fake, what was the forger’s motive? Was it ideological? Financial? Just a bizarre prank gone wrong?

“For many people, there is a lot at stake — personally, professionally, or both — when it comes to Christian origins and the life of Jesus,” said Stephen Davis, an early Christian scholar at Yale University who has not participated in the debate, in an email. “And these concerns are amplified by media interest and the echo chamber of online forums. I think we all — scholars and readers alike — love a good mystery that requires us to put on our Sherlock Holmes sleuthing hats and figure out, ‘Whodunnit?'”