“If you are walking in the woods and find an eagle feather, can you keep it?”

“If you are walking in the woods and find an eagle feather, can you keep it?”

This was just one of the intriguing questions that raptor rehabilitator Tom Ricardi asked sixth grade students at Gateway Regional Middle School last week. The answer was, “Absolutely not, unless you have a special license or are a Native American.”

“We’ve learned about ecosystems and we’ve learned about predation,” said sixth grade teacher Ruth Harper, from Gateway Regional Middle School. “Now we will see how this knowledge is put into practice through birds of prey.”

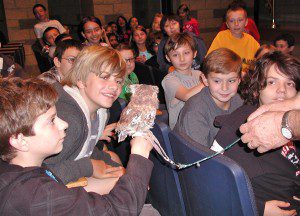

Harper was introducing Ricardi, a retired Massachusetts Fish and Wildlife Game Warden who now runs the Massachusetts Birds of Prey Rehab Facility from his home in Conway. Ricardi brought six raptors (birds of prey) to the school to give students a hands-on look at the unique abilities of each bird.

Ricardi takes in injured birds and releases them back into the wild if they fully recover from their injuries. “These birds are too injured to be released and survive,” he explained, as he began the process of showing a Great Horned Owl, Eastern Screech Owl, Turkey Vulture, Peregrine Falcon, Kestral, and Bald Eagle.

“Wildlife today is in serious trouble, not only in America but all over the world,” Ricardi told the students. “Habitat loss is probably the biggest problem, due to expanding development and increased use of the environment.” Ricardi also credited pollution and global warming for their impact on the ecosystem.

The facts he shared with students on these birds were, indeed, fascinating. Great horned owls have very little sense of smell and are one of the few predators that will hunt and eat skunks. He described the turkey vulture as a perfect scavenger, whose featherless face helps him stay clean and prevent disease. The turkey vulture has a single nostril that cuts completely through the beak, resulting in an incredible sense of smell that helps the bird locate dead animals.

At his facility, Ricardi is also working to rebuild the bald eagle population, which became endangered in the 1980’s. He explained that bald eagles mate for life, but lay their eggs several weeks apart. As a result, one eaglet is substantially larger than the other and gets the lion’s share of the food, jeopardizing the survival of the second fledgling. Wildlife personnel have begun removing the second egg before it hatches and giving it to Ricardi to incubate. Once the eaglet begins to hatch, Ricardi places it in “nest” that includes a mirror, which prevents the bird from imprinting on human foster parents. Ricardi feeds the eaglet using a bald eagle puppet, which he maneuvers to mimic the movements of the adult birds. When the eaglet is large enough, they band the bird to monitor it throughout its life span and return it to an eagle’s nest. To date, this has been done 38 times.

Ricardi finished his presentation by talking about careers that work with wildlife.