WESTFIELD-The Dever Stage in Parenzo Hall at Westfield State University was the recent setting for a “socially distanced recording” for the sixth album by composer Nicholas Quigley.

Quigley, who was joined by collaborators Alexander M. Thomas, D.M.A., visiting lecturer in piano at Westfield State, and Gregory Mahan, recordist and mastering engineer, has felt “fortunate” to work with them on several albums.

Composer Nicholas Quigley recently wrapped up a socially distanced recording at Westfield State University with two collaborators. (SUBMITTED PHOTO)

“Normally this scale of project should take at least a few days to record, but because they devoted so much of their professionalism and artistry to doing work before stepping on the recital hall stage, it only took us one four-hour session,” said Quigley, from his home in Portsmouth, R.I.

Quigley, a music teacher in the Fall River Public Schools, explained that the men had “completely formed ideas” from meetings on the Zoom platform so they knew the direction they wanted to take in terms of interpretation and recording aesthetics when they all met at Westfield State.

“We ended up having fairly clear roles the day of, and only a couple of conversations over minor details,” said Quigley. “The result is a record which captured and plays the music I composed in a way I couldn’t have ever imagined it before.”

Thomas shared a similar sentiment.

“It’s always a unique experience collaborating with a composer in real time,” said Thomas. “As classical musicians it’s something that unfortunately rarely happens. It’s remarkable for its unique balance of individual expression and faithful interpretation. “

Thomas added that Quigley allows the musician the freedom in his compositions to “breathe life into the music” where traditional scores take a more restrictive and prescriptive role.

Alexander M. Thomas, D.M.A., visiting lecturer in piano at Westfield State University, and Gregory Mahan, recordist and mastering engineer, recently collaborated with composer Nicholas Quigley on a full-length solo piano album. (NICHOLAS QUIGLEY PHOTO)

“Doing this over Zoom was a unique experience but one that I have become quite acquainted with having taught applied piano lessons virtually to Westfield State University students during the spring semester,” said Thomas.

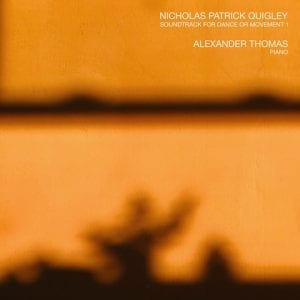

The album, titled “Soundtrack for Dance or Movement 1,” in 13 movements for solo piano, is available for purchase or streaming on multiple platforms, including Spotify, Apple Music, the iTunes Store, and Amazon Music.

A YouTube link featuring one of the movements can be heard at https://youtu.be/35DFwSAOQPw.

Thomas noted that as the performer, he was able to play virtually during meetings, however, he was concerned that the sound quality impacted the way the performance was perceived with limitations in sound quality.

Nicholas Quigley just released his new album, Soundtrack for Dance or Movement 1, which was recorded at Westfield State University. (NICHOLAS QUIGLEY PHOTO)

“In this situation it was harder to work on the small nuances of musical phrasing and was more meant for mapping out the bigger ideas such as character, color, and tempo,” said Thomas. “Between rehearsing and recording this experience has shown me that despite the virtual connection we can make these days we are still very far away from being able to communicate musical ideas as powerfully as a live performance. This gives me a lot of hope for the value and future of live musical performance and its social value.”

Mahan, formerly of Lowell and now a new resident of Denver, Colo., concurred.

“As someone who has worked in and studied recording for years, it was incredible to feel the impact that live music has on me,” said Mahan. “I’ve written numerous papers, and even my thesis on how the aesthetics of recorded music become a part of the music itself. Still, I found myself overcome with emotions upon hearing Alex play through the first few movements of the album. When we took a break, I remarked to Alex and Nick how moving it was to hear acoustic music performed by someone other than myself for the first time since February.”

Mahan added he has always been appreciative of the creative process when working with Quigley.

“It’s a partnership with everyone involved,” said Mahan. “You can speak your mind even though there’s technically still a client and engineer relationship in effect. When we were first setting up, I told Nick that I wanted to break from classical convention and set up the microphones closer to the pedals and hammers of the piano. The result is a soft, percussive layer of mechanical noises throughout the recording, coming from the movement of parts within the instrument.”

Two microphones were placed inside a piano to hear nuanced sounds for Nicholas Quigley’s new album. (NICHOLAS QUIGLEY PHOTO)

Mahan noted that “taking the listener inside of the instrument” is a concept that fascinates him, and he was grateful that Quigley allowed him to run with an unconventional microphone placement.

Quigley is hopeful that listeners will “just pause for a moment” and take in the music – especially during these turbulent times.

“My music isn’t very complicated, and it’s rarely dense in terms of harmony or instrumentation,” said Quigley. “But I definitely attempt to treat musical ideas with games in each movement of this piece – adding or taking away a beat from a measure or phrase, slightly adjusting harmonies as time goes on.”

Thomas noted that taking on a recording of this size in a short amount of time was a “physical and musical challenge.”

“Maintaining focus and musical integrity for that period of time is something that we rarely experience as classical musicians, but working with Greg and Nick made the process that much easier and resulted in a finished product I think we are all proud of,” said Thomas.

Mahan said this project didn’t require much of an “edit” in the conventional sense of the word.

“We had complete takes of each movement that we wanted to use, so there was no need to splice takes together,” said Mahan. “The entire album, believe it or not, was recorded with just two microphones. The album went through a light mix, applying some necessary volume adjustments to make sure that the album had a more consistent dynamic range overall. I also heightened the sense of the room through the use of a simple reverb, modeled after the properties of Symphony Hall in Boston.”

Mahan added the mastering process, which readies an album for distribution to different platforms, was where he spent the bulk of his production process.

“Mastering music is a great challenge because it involves tweaking technical elements that need to fit outlined criteria for services like iTunes with the artistic considerations of the piece of music,” said Mahan.

Quigley explained that the music came to be throughout his time living in Boston as a graduate student of music education – when he sat down at the piano almost daily to improvise.

“This became a therapeutic ritual during which I would ring myself out of waters dirtied by navigating uncertain personal and professional footings, and becoming evermore enraged by social justice issues that are almost completely ignored in the field of music education,” said Quigley, adding, “and the more I learn, the white supremacist world at large.”

Quigley said before recording with Mahan and Thomas, he questioned whether the work was still relevant since it was now several years old.

“My thinking is that while I have personally recovered from the particular emotional state I was in while composing, I am currently sensing a similar depressed, contemplative, frustrated, energy whenever I check my phone or go to the store,” said Quigley, adding, “and it re-emerges in myself in response to what I imagine so many others in the world must be feeling.”

While Quigley originally composed the soundtrack through a process of “self-care,” and for the purpose of “self-expression,” his new hope for the music will allow listeners to more fully interpret and situate their own experiences.

“Perhaps through these processes we can better imagine taking our next steps, either for ourselves or our shared humanity,” said Quigley.