Rare and Endangered Species in Westfield

Rare and Endangered Species in Westfield

Westfield citizens can be proud their city is home to many unique and rare species and ecosystems. Along with a plethora of uncommon (and many imperiled) natural communities such as ridgetop pitch pine – scrub oak or small-river floodplain forests, Westfield has 31 species identified as rare, threatened or of special concern. Westfield has outstanding populations of Purple Clematis, the largest-known Circumneutral Talus Forest in the state and the state’s largest occurrence of Cornel-Leaved Aster. A few rare species include the Eastern Spadefoot toad (Threatened), Timber Rattlesnake (Endangered), Golden-winged Warbler (Endangered) and the Marbled Salamander (Threatened). And Westfield has one of only three known sites for the American Clam Shrimp (Special Concern) in Massachusetts, and one of a handful of confirmed locations of Agassiz’s Clam Shrimp (Endangered) in the world.

Why Protect Rare Species?

It’s important to realize why rare species are protected. All species and elements of our environment play an important part of Earth’s health and stability. For thousands of years Earth and its ecosystems have been able to adapt to changes imposed by human developments and alterations. It is Earth’s great diversity of life that gives it strength and stability in the face of change. However, the mid 1800’s industrial revolution paved the way for those developments and alterations to increase in severity and frequency. The problem stemming from the industrial revolution is not that we are altering the environment, but that we are altering the environment at a rate Earth is unable to buffer, or bounce back from. A simple analogy would be to think of the Earth as a giant Jenga® game where every individual component of the environment (earthworms, carbon, elephants, rocks, dandelions, water, clouds, soils, whales, etc.) is represented by a wooden block. The blocks are configured in a tower like structure where each layer of blocks covers the last layer in the opposite direction, giving the tower great stability. The goal of the game is to remove blocks of wood, one by one, without causing the tower to collapse. The game ends when the tower collapses. The question is which block will cause the collapse when removed? Very similar in our Earth-Jenga game, the stability, health and endurance of Earth’s ecosystems depend on the interactions, interconnectedness and interdependence of its “blocks”. No one can guess which block, when removed will tip the scales to the point of no return. And if that happens, we simply don’t have the knowledge or economic ability to restore these ecosystems. Where will we be then?

Are We in the Midst of the 6th Great Mass Extinction?

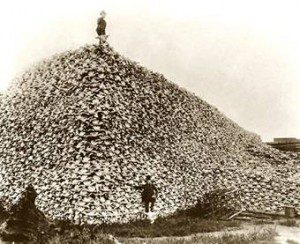

Scientists estimate 50 species go extinct every day compared to the natural (or expected) extinction rate of 1 species every 5 years. That means we are losing 1,825,000 species every hundred years, compared to the natural rate of only 20 species every hundred years. The six major causes for these extinctions are increased habitat alteration and loss, introduction of non-native species (invasives), increase human population growth, over-harvesting and over-hunting, degradation of natural resources and pollution. Scientists also estimate that 16,000 species are currently at risk of extinction. But we can curb these numbers. One success story is the American bison. Once numbering over sixty million, overhunting reduced that to a mere 750 individuals. With the efforts of conservationists and proper land management, Bison have now recovered and have a sustainable population. Some species are not so lucky. The world’s tiger populations have decrease 95% over the last hundred years, and there are so few Cheetahs left their genetic stability is in question due to related individuals inter-breeding. To learn more about species in peril, go to http://www.iucnredlist.org/.

How Are Rare Species Protected in Massachusetts?

Under the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries & Wildlife, protection of rare species is entrusted to the Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program (NHESP). According to their website, “NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program’s highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 256 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts.” To learn more about NHESP or to see a full list of rare species in any town in Massachusetts, go to www.nhesp.org

What Does it Mean When a Species is Listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern?

Under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act (Chapter 131A), endangered species are any species of plant or animal in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range and may include federally listed species. Threatened species are any species of plant or animal likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range, may include federally listed species, and any species declining or rare as determined by biological research and inventory and likely to become endangered in the foreseeable future. Species of special concern are any species of plant or animal which has been documented by biological research and inventory to have suffered a decline that could threaten the species if allowed to continue unchecked or that occurs in such small numbers or with such a restricted distribution or specialized habitat requirements that it could easily become threatened within the commonwealth.

Tension between developers and the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act has caused a few angered land owners to seek abolition of this law. Currently, the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act is being threatened by newly filed legislation in the state Senate. An Act Relative to Land Takings, filed by Senator Gale Candaras (D-Wilbraham), would repeal the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act by placing an impossible regulatory burden on the already understaffed Division of Fisheries and Wildlife and effectively undoing current protections for hundreds of at-risk species. Removing this law altogether is not the answer. Those at the state level need to reevaluate the act for its effectiveness and look for ways of improving the existing law.

Karen Leigh is the Westfield Conservation Commission Coordinator and can be reached by calling (413) 572-6281.