Construction continued on the Pochassic Bridge in Westfield in November. The state Department of Transportation closed the bridge in January 2010 due to structural deterioration. Estimated cost for the reconstruction was $2.7 million and the work is being financed with federal and state funding. The reconstruction is estimated for completion by spring. (File photo by Frederick Gore)

WESTFIELD – There was much hand-wringing during a recent City Council meeting, and much of it had to do with approving a funding request from Domus Inc. for the “Our House” project.

Proponents and opponents of the project packed the City Council Chambers to advocate for council support during the public participation phase of the session. Proponents cited the benefits to the community, while opponents cited the construction cost of $1.4 million as an exorbitant expenditure of public funds.

The council, following a protracted debate, voted 11-2 to approve the Our House funding.

The project will convert the former Red Cross Chapter house on Broad Street into a 10 single-room residency (SRO) facility, as well as include building an addition onto the existing structure. There will be an apartment for a resident supervisor in addition to student housing.

“This project is very expensive. The cost is too high,” At-large City Councilor Dan Allie said, voting against it. “Its not free money.”

Ward 6 Councilor Christopher Crean, a member of the Finance Committee, which discussed the Domus funding request prior to the council meeting, said that he was initially concerned about the appropriation, but that he had further investigated the project.

“The two big issues are the building cost and the social service aspect of the project,” Crean said. “The state sets the prevailing wage requirement. Eighty percent of the cost is due to state requirements.”

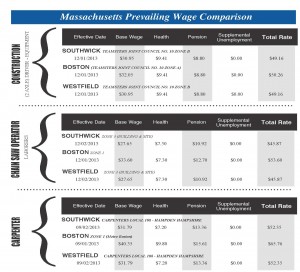

Enforced through the Office of Attorney General Martha Coakley’s Fair Labor Division, the state’s prevailing wage law sets a base wage for vendors who take on municipal contracts, along with health and pension benefits.

For example, a brick, stone or artificial mason who is a member of the Springfield/Pittsfield district of the Bricklayers Local 3 union working on a job in Westfield is entitled to a base wage of $36.56 as of March 3, which, in addition to health benefit pay of $10.18 and $16.31 towards the worker’s pension, totals their prevailing wage at $63.05.

However, a mason who is a member of the Boston District of Bricklayers Local 3 will earn a wage of $76.39, made up of a $48.16 wage, $10.18 for health benefits, and $18.15 for the worker’s pension.

These wages play a large part in driving up the cost of the procurement process for municipalities like Westfield and Southwick, both in the midst of large municipal building projects.

“The laws were put in to ensure a living wage,” said Karl Stinehart, chief administrative officer for the Town of Southwick. “And they’ve been in for decades.”

“It affects our school renovations (at Woodland Elementary School), anytime we pave a road, or work on a bridge,” he said. “The sewer and water tank projects, and the senior center project in Westfield are dealing with this, too.”

The wage law affects workers in multiple fields, including construction, marine drilling, school transportation, janitorial and cleaning, sweeping, outside electrical, rental of equipment, moving, trash and recycling, window washing, and dredging work.

While the logic behind a prevailing wage is that everyone has the right to a livable wage, some city officials say the current law chokes creativity in the way local governments spend their funds, and gained strength after the state uncovered mass corruption in construction and building.

“A lot of the prevailing wage stuff came about around 1929, but in the 70s, the Ward Commission was created because there was a lot of corruption in public building projects,” said Peter Miller, community development director for the City of Westfield, referencing a scandal which led to the conviction of two state senators on extortion charges for accepting payoffs from a construction management company handling the building of the University of Massachusetts’ Boston campus. “I think it (prevailing wage) has a place, but it takes creativity and motivation out of the process. Creativity in government is frowned upon.”

“It drives up costs, which is a primary challenge with a lot of these projects,” he said. “Massachusetts is a high-cost state, but by making projects 35 to 40 percent more expensive, it makes it more expensive for local governments. The deck of cards is stacked against us.”

“It can take five to twelve years to make an idea into a reality,” he said. “It took four and a half years from the time we found a site for the senior center to when the first shovel went in the ground. From conducting feasibility studies to the designing and drawing of the project to the three to four month process of getting a contractor, all these requirements add time and accountability.”

Westfield Purchasing Director Tammy Tefft agreed that the price increases for city contracts.

“It’s union-driven,” she said. “The price sometimes goes up by a third, if not more.”

Tefft also stated that the public needs to understand that increases in the prevailing wage occur over time.

“(The wage) depends on whether the contract is multi-year,” she said. “We have no choice but to pay it. The only way to avoid the wage increasing is to bid contracts out to one-man shops, but you can’t contract building and road projects out to one person.”

Tefft added that any time a project receives federal funding, workers are to be paid the higher of the two wages.

Labor advocates say that the prevailing wage was implemented to dissuade carpetbagging contractors from other states from coming to the Commonwealth to build.

“The prevailing wage is established through a survey of individual trades’ average wages and benefits.” said Jason Garrand, business manager of Carpenter’s Local 108 in Springfield. “The goal is to eliminate outside contractors from other states that would lower standards. It’s meant to eliminate out-of-state contractors coming in and taking money out of that community.”

Garrand argues that construction jobs can be dangerous, often expose workers to the elements, and are deserving of a living wage

“It’s ugly out there. It’s a young man’s game,” he said. “You look at the federal poverty rate, it’s $10,400 per person. I’ve seen plenty of contractors making only $15 an hour.”

Garrand rationalizes that a family of four with a stay-at-home mother cannot survive with a lone breadwinner earning that wage.

“You add it up, and the poverty rate for a young family is almost $41,000.” he said. “So if a contractor works 2,000 hours a year, he earns $30,000. Think about it, to hire your neighbor’s kid to babysit your kids, you pay around $10 an hour, and you’re bringing in only $15 an hour?”

State Representative William “Smitty” Pignatelli (D-Lenox) was an electrical contractor prior to his foray into state politics, and believes a middle ground needs to be found on prevailing wage.

“When I was in the business, I never even bid on prevailing wage jobs,” he said. “I was paying my electricians $10 an hour and I wasn’t interested in them getting $32 an hour to work for a few hours.”

Pignatelli, whose 4th Berkshire District includes Blandford, Chester, and Tolland, said the prevailing wage law is designed to level the playing field between union and non-union workers.

“If it’s a $2 million renovation to a town hall, that’s one thing,” he said. “But if you hire a plumber to fix a toilet for $100, and it becomes a $500 job because of prevailing wage, we need to take a different look at it.”

Pignatelli said that several years back a statewide ballot to repeal the prevailing wage was defeated resoundingly.

“I’d love to see unions and municipalities sit down and create a threshold,” he said. “That we’ll pay a prevailing wage only for projects that go over a certain price, which would mean the procurement process would have to be tightened up.”