WESTFIELD – Ukraine, the eastern European nation which borders the countries of Russia, Belarus, Poland, Romania, Moldova, and Slovakia, has been embroiled in tension since the beginning of the Euromaidan in November 2013, a series of demonstrations in the Ukrainian capital of Kiev calling for further integration with the European Union and in opposition to the pro-Russian government of President Viktor Yanukovych.

WESTFIELD – Ukraine, the eastern European nation which borders the countries of Russia, Belarus, Poland, Romania, Moldova, and Slovakia, has been embroiled in tension since the beginning of the Euromaidan in November 2013, a series of demonstrations in the Ukrainian capital of Kiev calling for further integration with the European Union and in opposition to the pro-Russian government of President Viktor Yanukovych.

A boy holds a Russian flag as he gathers with others at a square to watch a televised address by Russian President Vladimir Putin to the Federation Council, in Sevastopol, Ukraine, Tuesday. Putin on Tuesday fiercely defended Russia’s move to annex Crimea saying Crimea’s vote on Sunday to join Russia was in line with “democratic norms and international law.” (AP Photo/Andrew Lubimov)

The demonstrations came to a head last month, as the Yanukovych government was overthrown, and the president subsequently fled to neighboring Russia.

Since the downfall of the government, the dissent has spilled over into Crimea, an autonomous peninsula which sits on the country’s southern end on both the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, whose population has a large Russian minority, and is now seeking to realign itself with Russia.

With Crimea now in Russia’s pocket, the world anxiously awaits Russian President Vladimir Putin’s next move, no one more so than Westfield residents Igor and Vitaliy Khomichuk.

People gather at a square to watch a televised address by Russian President Vladimir Putin to the Federation Council, in Sevastopol, Ukraine, Tuesday. (AP Photo/Andrew Lubimov)

“We don’t agree with Mr. Putin’s politics,” said Vitaliy, 28, of Westfield, whose family’s property on the city’s west side is plastered with signs bemoaning Putin’s actions. “We came from the western part of Ukraine, and have nothing against the Russian people. We fought alongside them in World War II. We came from the same bloodline.”

Khomichuk, who works with his father Igor, 51, the owner of Good Choice Home Improvement, Inc., a Westfield-based general contracting company, said his family came to the United States almost a decade after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, and keeps in contact with many friends in his homeland.

People gather at a square to watch a televised address by Russian President Vladimir Putin to the Federation Council, in Sevastopol, Ukraine, Tuesday. (AP Photo/Andrew Lubimov)

“It seems like now, even my Russian friends on Facebook, they call the western part of Ukraine ‘fascists’, which is untrue,” he said. “There are some people who take it to an extreme to some degree, but a huge part of Ukraine just wants change and a better government.”

Khomichuk said Yanukovych stole from his people, and that Russian forces are moving into Crimea to “protect Russian people” living there.

“We used to go to the Black Sea and relax,” Khomichuk said, giving an idea of just how close the two nations are geographically and culturally. “Russia says it’s their land, which is untrue.”

Igor Khomichuk, the family patriarch, said that he has four children, three boys and a girl, and that two of his daughters-in-law are from other Slavic nations, emphasizing the goodwill that is shared by most countries in Eastern Europe.

City council workers clear a barricade on a road leading to Kiev’s Independence Square, Ukraine on Tuesday. Kiev authorities have cleared a number of barricades around Independence Square in an effort to ease traffic congestion. (AP Photo/David Azia)

“One daughter-in-law is from Russia, another from Ukraine, another from Moldova,” he said in his thick accent. “We’re all very friendly.”

Vitaliy reiterated that he has many Russian friends and that “nothing is going to change” between them despite their differing views on the turmoil.

“They take very opposite sides,” he said. “We just want better for our country. We don’t want to fight with Russia. People just want a better life. The European Union can help level life a little more, and for some reason Russia doesn’t want that.”

Local residents prepare to toast as they watch a live broadcast from Moscow showing the signing of documents on Russia’s annexation of Crimea, in Simferopol, Ukraine, on Tuesday. With a historic sweep of his pen, President Vladimir Putin signed a treaty Tuesday to annex Crimea, describing the move as correcting past injustice and a necessary response to what he called Western encroachment upon Russia’s vital interests. (AP Photo/Ivan Sekretarev)

The elder Khomichuk recalled his own father, who now lives in South Carolina, being imprisoned for 15 years by Soviet leader Joseph Stalin for being a Christian, and fears that Putin, a former officer in the KGB, the Soviet Union’s notorious state security agency, is up to his old tricks.

“He was imprisoned in Sakhalin, a prison near Siberia,” Igor said. “Putin is a liar. Propaganda is very powerful. In Russia, old people are very poor. They have nothing, no Internet, nothing. Putin is God to them.”

Igor added that when his father was freed from prison in 1953 following Stalin’s death, he and his family were relocated to Serbia, as former prisoners were often sent to different parts of the Soviet Union, places such as Crimea, which has become a flashpoint of tension in the current conflict.

“We have Russian neighbors and we get along with them,” Vitaliy said when asked of whether tensions abroad are now creating animosity here at home. “We have friends in church from all over Eastern Europe. It shouldn’t be Ukraine versus Russia. It should be Ukraine versus corrupt government.”

The younger Khomichuk spoke of last fall’s Ukrainian revolution as “justified”, but that he fears that war could be on the horizon.

“We hope there is no bloodshed,” he said. “All of the younger people (in Ukraine) are pro-European Union. They want better because they’re well-informed. Those people in Crimea and the eastern part of Ukraine, they’re more toward Russia because of what they’ve been fed. If they’re being told lies, what are they going to believe?”

Both of the Khomichuk’s believe the United States and the European Union can put an end to the tension.

“I believe the American government and European Union can stop Putin,” said Igor. “These governments must stop Putin. He hasn’t changed from when he worked in the KGB.”

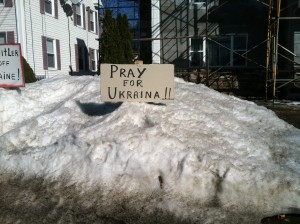

One of several signs of solidarity on the property of Igor Khomichuk on Westfield’s west side. (Photo by Peter Francis)

“I’d like to see them put economic sanctions in,” said the younger Khomichuk. “We don’t want Ukraine to split in two.”

When asked of whether the majority of the Slavic community in Westfield shares his family’s sentiments, Vitaliy gave an answer that could be expected.

“Most Ukrainians do. Russians… I can understand them sticking up for Russians. I accept that, but I don’t agree with them,” he said. “I see people on Facebook on multiple discussions going against each other and I say ‘Hey, you can’t do that. We live here, we’ve got to come to terms, we’ve got to be together.'”

Vitaliy, who arrived in the U.S. at age 14 and became an American citizen four or five years ago, said he has been referred to as Russian for as long as he’s been in the Westfield area.

“I’ve been called Russian my whole life. When I went to high school, people did not know Ukraine. It is smaller than Russia,” he said. “And I have no problem (with that). I had Moldovian friends who were called Russian. Everyone was called Russian. It was no problem.”

Igor then showed a YouTube video on the family computer of Ukrainian youths singing their national anthem in English, a moving scene which gives his son and him hope that a stronger, unified Ukraine will emerge from the struggle and strife.

“We pray to God there will be no war,” Vitaliy said, as his mother Yevgeniya and his wife emerged from the living room holding his infant son, Maksim. “I want to take him there someday. I want him to see Ukraine.”