BUFFY SPENCER, The Springfield Republican

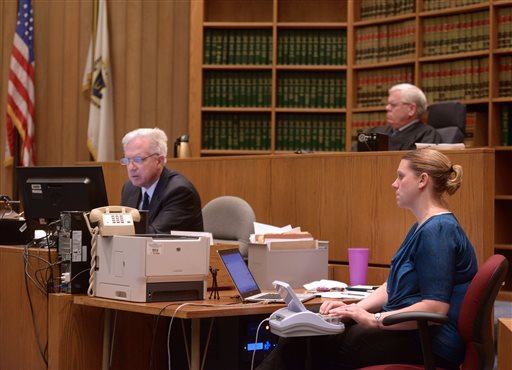

SPRINGFIELD (AP) — When a criminal trial is about to kick off in western Massachusetts, the action doesn’t start until the court reporter takes her seat below the judge’s bench.

That’s because she (36 of the 40 court reporters employed by the Massachusetts Trial Court statewide are women) is responsible for making an accurate record of the trial. That record is crucial because it will be used in appeals of murders and other serious cases as well as for other purposes by lawyers and judges.

The long history of having human court reporters may be ending soon, replaced by technology.

The move has proponents confident, but opponents are very wary of the change and rue the expected loss of court reporters in the courtroom.

The Trial Court is in the process of implementing a new digital recording system, For the Record (FTR), in 455 courtrooms across the state — first slated for the Superior Court and other courtrooms in buildings that house a Superior Court, according to a Trial Court spokeswoman.

The contract is $5 million for equipment and installation in the 455 courtrooms.

The 40 court reporters employed by the state Trial Court haven’t been told their fate by the Trial Court. They have been told — indirectly from the Trial Court via their union — their jobs are not guaranteed after June, the end of the state fiscal year.

It’s a nervous time for court reporters, many of whom have done their job for decades.

In addition to the demographic regarding gender, all but three of the 40 court reporters statewide — who make $82,000 per year — are over 40 years old.

A Trial Court spokeswoman provided the following statement:

“FTR is now operational in Plymouth and has been installed in Salem, and installation is under way in Worcester. All work is being done on weekends, so as not to disrupt court business.

“The Trial Court Human Resources Department has been working with the union that represents Court Reporters regarding the impact of the new digital system on Court Reporters. No final decision about employment status has been made.”

The spokeswoman said the transition to digital recording represents a significant change for the Trial Court and will also allow for court transcripts to be produced more quickly.

In an email to “Colleagues in the Superior Court” last month, state Trial Court Administrator Harry Spence wrote, “Discussions by judges or other court officials with individual Court Reporters on their employment status are to be avoided, as those discussions may constitute direct dealing, which is not permitted by the collective bargaining law. Court reporters who have such questions should be directed to contact Local 6.”

The move from people to technology has many worried, although Tony Douglass, the head of FTR, said there is nothing to worry about — whatever the concern, they have it covered.

There is another level of concern too, and that is personal. Many court reporters, including the five women who work as court reporters primarily in Hampden Superior Court, are considered valued members of the court system.

A judge at trial can ask the court reporter to read back the last question or answer when he or she is ruling on an objection. The court reporter is the one who gets the correct spellings of names and locations for the record.

The court reporter is the one who alerts the judge when a witness is talking too quietly to be heard by her. A court reporter is the one who prepares the clean and official written transcript to be used for future proceedings in a case.

The FTR website describes the company as follows: “FTR solutions are used the world over, across 27,000 installations in 65 countries and 50 US States. To support our global customer base takes a truly global operation. Our development operation, FTR Labs, is headquartered in Brisbane, Australia, with an additional development office in Perth. In the Americas, our sales and support team is based in Denver, Colorado, while we also have a presence throughout Asia Pacific, Europe, the Middle East and Africa.”

Christie Aarons, one of the court reporters who works in local Superior Courts, said the court reporters just want to be treated fairly.

“As citizens we are concerned that the importance of an accurate record is getting lost in a rush to digitize the Trial Court,” she said. “The record of the proceedings protects every person who walks through these courtroom doors, both victims and accused.

“The record is the transparency that the Trial Court must have to effectively administer justice. If the record is of poor quality or nonexistent, then cases have to be retried and hearings have to be done over, and that costs the taxpayers money, it costs the court and the parties time, and most importantly it adversely affects both victims and the accused,” Aarons said.

She said a wise plan would be to use digital technology in conjunction with the court reporters, use court reporters in serious felony cases, and leave it at the judges’ discretion to decide which is appropriate in each case.

Aarons said court reporters spend $10,000 out of their own pockets, including: steno machine, $4,000 to $5,000; transcript software, $4,000; and money for laptops, printers and office supplies such as toner, discs and paper.

“Our job doesn’t end at the end of the court day. We type transcripts at home on nights and weekends,” she said.

Laura Gentile, Hampden Superior Court clerk, said she has great concerns the FTR recording system is being implemented too quickly. She said Plymouth County, where it is being used, is not comparable to Hampden County or other large counties.

She said assistant clerks who sit in trials are keepers of the record, not makers of the record like court reporters. The clerks have their own jobs to do in the courtroom and should not be expected to constantly monitor an audio recording system, she said.

Clerks tag and keep exhibits organized and ready. They fill out paperwork for jurors. They also need to leave the courtroom at times for other duties, she said.

Court reporters have been creating the trial record throughout history because it works, she said. “In my opinion that’s why they can’t be replaced, because nothing can replace them,” Gentile said.

Nikolas Andreopoulos, a private practice lawyer representing many defendants in serious criminal cases including murder, said if court reporters are let go by the Trial Court, it will be a loss for the court system.

“You can’t really trust technology over seasoned court reporters,” he said.

Andrew Klyman, head of the Committee for Public Counsel Superior Court office in Springfield, said he thinks it’s overall a bad idea to function without court reporters in the courtroom. He said an audio recording system will lack the human element. A machine may not be able to pick up everything happening in a courtroom, Klyman, who represents some murder defendants, said.

Linda Thompson, a private lawyer who has long represented murder defendants as well as people accused of other serious offenses, said, “I like people rather than machines.” She said she likes the ability to talk to court reporters directly to order transcripts or parts of transcripts.

“I think it will make it more complicated in court,” Thompson said. “Frequently gaps have to be filled in the record.”

A trial is a fluid thing with issues arising throughout, she said. “I don’t think you can manage it by machines,” she said. “There are literally times when a court reporter will look at judge and say, ‘I can’t take that down, too many people are talking.'”

She said there are times she wants to get a piece of transcript for the next day to use in closing argument and she can’t imagine how an audio recording system will handle that.

Hampden District Attorney Anthony Gulluni had no comment on the installation of FTR or the possible loss of the court reporters, according to his spokesman, James Leydon.

Douglass, FTR president, said he has of late been based in Williamsburg, Virginia. There is a Boston project office as well as space being used in several courthouses, he said.

FTR, he said, will make an excellent quality recording in the courtroom. The recording will be kept in a central data base.

FTR does not produce a written transcript.

“You still require a court reporter to produce a transcript,” Douglass said.

Although Douglass said a court reporter is still needed to produce a written transcript, transcripts can be produced by people who are not Trial Court-employed court reporters.

Audio recording of civil trials is already used, with a system called JAVS (Jefferson Audio Visual Systems.)

The state Trial Court website has a “trial court approved transcriber list” from which anyone wanting a transcript of the civil proceeding can contract for one. The transcribers, who often work for private companies, are not court employees.

Douglass said the company is putting in very high quality recording systems. There will be a detailed assessment of every courtroom with “targeted amplification and reinforcement,” Douglass said. Multiple microphones will be placed where needed, he said.

As for playing back a previous question or answer, Douglass said the recording can be played back to any point. Whoever is monitoring the recording system in a courtroom is the one who would find the section a judge wants played back.

As to who in the courtroom will be constantly monitoring the system to see it is working, Douglass said it would be up to the specific court. It could be the assistant clerk, it could be a courtroom monitor, it could be a court reporter, it could be a probation officer, he said.

In Hampden Superior Court, a monitor is used in courtroom one, the courtroom that handles arraignments, pre-trial conferences, scheduling and other matters. That courtroom does not handle trials.

The courtroom monitor is a person who continuously ensures that the audio system being used there (not FTR) is picking up everything and tells people when they need to step closer to the microphone or speak up. The pay for current courtroom monitors is significantly less than for court reporters.

There is an expectation that the Trial Court may hire some additional courtroom monitors, but certainly nowhere near the 40 court reporters who may lose their jobs. The Trial Court spokeswoman said it is working with FTR to see what the needs will be.

Monitors are not paid to produce written transcripts, their role is to make sure the audio system is picking up everything in the courtroom.

Whoever is monitoring the system would need to alert the judge if a witness — or anyone else for that matter — is not speaking loud enough or answering with a nod of their head instead of verbally, Douglass said.