WESTFIELD – Roy H. Saigo, a Japanese American from California, experienced Asian hate crimes from a young age. From being sent to an internment camp to being denied food at the local market, Saigo, Westfield State University’s interim president, has experienced racism his entire life.

At a time when hate crimes against Asian Americans have ramped up and continue to remain high, Saigo offered his perspective April 5 during a virtual dialogue.

Westfield State University hosted the event in part to celebrate Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month in April. It was titled, “Truth in History, Positionality, and Solidarity in Practice: A Leadership Dialogue with President Saigo.”

Much of Saigo’s discussion centered around his early childhood and his experience as one of tens of thousands of Japanese Americans who were forcibly sent to internment camps during World War II after President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued executive order 9066. This order authorized the secretary of war to prescribe certain areas as military zones, clearing the way for the incarceration of Japanese Americans during the war. According to The Smithosonian, nearly 75,000 American citizens of Japanese ancestry were taken into custody.

Saigo asked the dozens of student attendees to consider the links between anti-Asian attitudes in the 1940s and those same attitudes in 2021. He also asked them to imagine what would be going through their minds if they were put in the same position that he and his family were put in nearly 80 years ago.

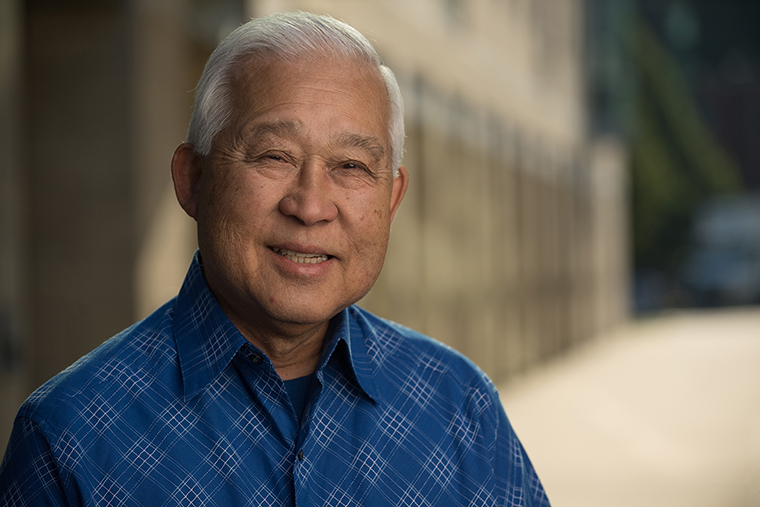

Westfield State University Interim President, Roy Saigo, July 2020. (WESTFIELD STATE UNIVERSITY PHOTO)

“You changed your culture, your face, your language, your food, your customs, but now, because of your genetics, you are being moved to unknown places,” said Dr. Saigo, “What do you feel? Disbelief? Fear? Indignation? Panic? Likely hopelessness, and despair.”

Saigo, his brother, Takeshi, his sister, Chiyo, and their parents were originally from northern California before they were moved to their camp. They were first sent to an “assembly center” in Sacramento before being shipped to the relocation camp in Gila River, Arizona. The assembly centers were quickly prepared as temporary housing before the Japanese-Americans were assigned to their internment camp. The internment camps consisted of multi-family military-style barracks and communal services buildings that housed mess halls, latrines, and shower houses.

As people settled into the internment camp, schools were set up and community activities were organized.

“The homes in the camp were horse stalls with manure piles often stacked nearby,” said Saigo of the assembly centers, “Last night you were in your own cozy bed tucked under your blankets with a nice pillow. Tonight, you are in a horse stall, the manure is still fresh.”

Despite the treatment of the Saigo family and thousands of other Japanese Americans at the hands of the U.S. government, Saigo said that there was a sense among the Japanese community that they should continue to be patriotic Americans. He later said that there was no real time for them to feel anger, even after they were able to leave.

“There was no time for anger. We were afraid after we got out of the camp. We were identifiable due to our appearance. Our homes, automobiles, jobs, and farms were gone. We had lost everything, but we kept our anger inside,” said Saigo, “Everyone just wanted to get back to “normal life,” to have peace and stability, and to try to recapture and rebuild our lives. Older Japanese, however, felt a sense of shame; they were ashamed they had been placed in that situation and had been unable to protect their families.”

He said that there was a sense among the Japanese American community to keep one’s head down and continue to be the model citizen. Though they were released and the war had ended, anti-Japanese attitudes persisted in some form for most of Saigo’s life.

“It was difficult to buy food because the stores did not want to appear friendly to the ‘enemy.’ However, when we moved to work on a farm in the country, an enterprising person would drive his truck filled with groceries to sell away from the city. We were fortunate in the country to raise chickens and grow most of the vegetables that we needed to sustain our family,” said Saigo.

Saigo was a college student during the Vietnam War, and he said that he and his siblings felt “ostracism and the absence of respect and opportunity in social standing and professions.

“The brutal, unprovoked attacks now are evidence of the prejudice and hate that are still simmering. No matter the foreign policy, this ability to hate and strike out is, unfortunately, embedded in people. Depending on world events and politics of the moment, South Asians and Muslims also have experienced attacks in the past two decades,” said Saigo.

He is referencing the recent rise in attacks on Asian Americans that have been in large part attributed to anti-Chinese attitudes drawn from the COVID-19 pandemic, which is believed to have originated in China.

A recent report from the Stop Asian-American and Pacific Islander Hate organization found that between March 19, 2020 and Feb. 28, 2021, there were 3,795 incidents of hate or violence towards Asian Americans. In the same time period the prior year, there were 2,600 similar incidents.

“This latest pandemic has created a difficulty that we need to stand up and confront the issue,” said Saigo.

He admitted that he has in some cases felt the need to shut a person down because of their behavior and biases towards him, though he said that shouting and getting visibly angry will do little to solve the problem. Instead, he said that the best option is to film the incident, but to also remain calm and try to have a real conversation with the person.

“Shouting never resolves anything. It just makes people feel uncomfortable,” said Saigo.