Michael Ballway

Maybe this is a strange thing for a local journalist to admit, but I’ve never been able to understand voters.

Every four years, they turn out in droves to weigh in on the presidential race. Even though the Bay State hasn’t voted for a Republican since Ronald Reagan, partisans on both sides rush to make their one small addition or subtraction to the inevitable landslide.

Even in the midterms, once the television ads start up, voters start paying attention to congressional races and the governor’s race, and a respectable number go the polls to decide who gets to sit on Beacon Hill and Capitol Hill. The races are at least more competitive — witness the several Republican governors in recent history — but realistically speaking, Westfield will always get the congressman Springfield votes for, and the governor Eastern Massachusetts wants.

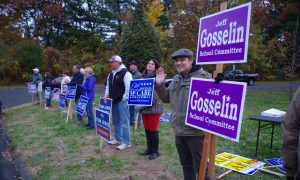

Somehow that enthusiasm doesn’t translate to the odd-year elections, when the stakes are seemingly lower, but a lot closer to home. Westfield has a contested mayor’s race, a six-way School Committee race and a competition for Ward 1 city councilor, but today’s tally is unlikely to break any turnout records.

That’s completely backwards. In a deep blue state, city elections are the place where your vote counts the most.

When’s the last time a governor won his seat by less than 39,000 — that is, a margin closer than the entire city population of Westfield? When’s the last time the presidential race in Massachusetts was as close as even a million votes?

Ask me about a local race, though, and I can immediately think of two local examples where a small number of voters made a difference.

Just over the town line in Granville, there’s a Selectboard member who owes her seat to precisely one voter. Nicole Berndt unseated a 30-year incumbent by a tally of 182-181 in the town election of 2018. One voter made all the difference — which means that each of her 182 voters, by choosing to participate that day, was the “one voter” who flipped the election.

And then there’s the most recent example in Westfield itself. The two candidates for mayor are the exact same ones who ran in 2019. And last time it was close. After a recount, just 90 votes separated Donald Humason Jr. from Michael McCabe. In a city the size of Westfield, 90 votes isn’t much. If five Humason voters at each polling place had changed their minds at the last minute, McCabe would be the mayor today. Pick one apartment house in each downtown precinct, and one cul-de-sac in each outlying ward, and flip the votes of five adults. Completely different result.

Maybe there aren’t 45 voters in Westfield who would change their preference. But there certainly are 90 people who aren’t voting.

The selectboard member who lost that Granville race three years ago didn’t lament the folks who voted for his opponent. Instead, he wished that more of his own supporters had shown up, instead of staying home. Likewise, with city clerks around the region predicting turnouts well below 50 percent for this year’s mayoral races, there is likely an awful lot of people planning to sit out today’s vote in Westfield. It wouldn’t be too hard to find 90 people in that group who can do a little reading and develop an opinion on whether Humason or McCabe has the right ideas, experience or style for the city.

Remember how excited you were to vote for Trump, or to vote for Obama, or to vote against them? You circled that Tuesday on your calendar. You told all your friends how important it was to choose your candidate for president. You posted a selfie at the polling place.

And if you lived in Massachusetts, your vote meant very little. Massachusetts’ 11 electoral votes went to a Democrat regardless of whether you and your neighbors were part of the majority or the minority.

Your heart was in the right place, though. Voting is important. Choosing the right leaders is important. You should be excited to vote, even if you know how it’s going to turn out.

Well, today everything is in the right place. The mayor sets the agenda for the city, and the city councilors and School Committee members write the policies that affect us on a local level. But more than that, we don’t know how it’s going to turn out. This election is where you, the individual voter, can truly make a difference.

There’s no national media telling you that this is “the most important election ever.” And this election likely won’t make much of an impact on United States history.

But this is the election where you can make the most impact. Only if you show up and vote, though.

Michael Ballway is the editor of The Westfield News.