Dr. Robert Brown presented a lecture titled “A History of Downtown Westfield” to a packed crowd during the Westfield 350 Lecture Series. (LORI SZEPELAK PHOTO)

WESTFIELD- The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic is often compared to the 1918 H1N1 Spanish Influenza pandemic due to both diseases being in the same class of virus and the speed at which both spread throughout the globe.

The City of Westfield was not left unscathed from the 1918 pandemic. The city was hit about as hard as the rest of the country by the deadly virus. Untold tens of millions were killed globally by the end of the pandemic in 1920.

Local historian Robert Brown has been actively researching how the virus impacted Westfield and what the local response was to the situation. He said he plans on giving a lecture on the topic when the COVID-19 pandemic is over, so he can do so in person.

In his research, Brown found many similarities, and some differences between the 1918 Flu and COVID-19 pandemics.

Brown did the bulk of his research by scouring the Westfield Athenaeum’s online archives of Westfields historical newspapers. The Valley Echo and The Hampden County Leader were the two papers of record at the time the Spanish Flu had hit Westfield. Brown also used information from the book: The Great Influenza, by John M. Barry.

“When this struck it 1918, it was only in the short term,” said Brown, “There was only about two-and-a-half months of it in Westfield even though it was around for two years.”

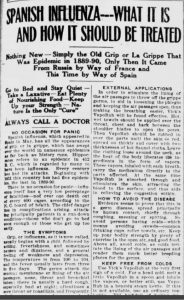

An article about the Spanish Flu that ran on page 3 of The Valley Echo on Dec. 1, 1918. The article was found in the Westfield Athenaeum’s online archives.

The virus was originally detected in the spring of 1918. Though it is called the Spanish Flu, it is actually believed to have originated in a pig farm in Kansas. It is only called the Spanish Flu because Spain was a neutral country in World War One, which was nearing its end at the time, and was not subjecting press to the same censorship as the belligerents of the conflict. Thus it was widely believed at the time that Spain was especially hard hit.

The outbreak remained mostly in the western U.S. until September, when massive outbreaks struck the military camps in Boston and Philadelphia. Before then, news of the outbreak hadn’t traveled very widely due to the lack of mass communications. In early September, The Valley Echo and the Hampden County Leader began publishing obituaries citing a cause of death of “pneumonia” or “Spanish Influenza,” but there was little frontpage coverage of the pandemic in the local papers. World War One understandably dominated the headlines at the time.

Brown described The Valley Echo as a local gossip paper, while The Hampden County Leader was a more traditional newspaper that covered local, national, and international news. He said that the Echo provided about twice the number of obituaries as the Leader, because the Leader was omitting the deaths of immigrants from their paper.

From what Brown could gather from the Athenaeum’s newspaper archives, about 180 people died in Westfield from the Spanish Flu in 1918. Between 60 and 70 children were left as orphans because both of their parents passed away. Westfield at the time had about half the population it has now. Seventy-four people are confirmed to have died due to COVID-19 in Westfield as of Dec. 1, 2020.

The Leader also blamed the spread of the deadly virus on immigrants, a sentiment that was echoed in the early parts of the COVID-19 pandemic when Asian-Americans were often wrongfully subjected to discrimination due to the virus’ origins in China.

Noble Hospital had only just been constructed, and was not able to take in every patient. Thus, most people who succumbed to the virus in Westfield died in their homes. The medical care at the time consisted of all volunteers. There was no ambulance in town, so a handful of people who had cars volunteered to be drivers. A volunteer kitchen was set up to deliver meals to the sick.

At some point, Brown said, the crisis in Westfield escalated to the point where the Army National Guard was made to police the streets of Westfield’s immigrant neighborhoods for two weeks. The military police enforced the use of masks, which were made mandatory in Westfield as the virus spread. The masks of the time were not as effective as the medical-grade masks in use today, but were still believed to be able to slow the spread of the virus.

Brown said that, like in the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a resistance to mask mandates despite ample evidence of their effectiveness. There were also local churches that resisted the notion of closing their doors to close the spread.

Brown said that the Catholic and Baptist churches were resistant to the idea of closing, while the Methodist churches and other organizations did not protest the idea too much.

“People refused to believe it could happen to them, until it happened to them,” said Brown.

While the two viruses are similar in structure and how they make people sick, the 1918 flu affected different groups of people in different ways from COVID-19. With COVID-19, it is mostly people over the age of 50 or those with comorbidities that are being the most severely impacted.

With the 1918 flu, it was people aged 20 to 40 who made up the bulk of the deaths, which is made evident by many of the obituaries in the local papers consisting of U.S. soldiers from Westfield who died from the flu.

It is not exactly known why this was the case, as most people in that age group should have a relatively strong immune system. Brown said one theory is that the immune system went into overload, which often killed the person.

Another theory relates to the idea that there would be a flu epidemic every 10 years or so in that time period. Every 20 years, that flu epidemic would be extremely bad. It is believed by some that those who survived an earlier flu epidemic may have had some immunity to the 1918 flu. Those who were younger and thus not around during those epidemics would not have had that immunity, and would have been more severely affected by the virus.

A vaccine was never properly developed for the 1918 flu. Scientists at the time debated whether many of the cases were just a bad case of pneumonia or if it was a new disease with pneumonia as a symptom.

“The medical researchers focused on pneumonia. That early, people didn’t know what a virus was. They tried to develop a pneumonia vaccine,” said Brown.

The significant higher death toll in the 1918 flu compared to COVID-19 so far can be largely attributed to the lower quality medical care that was available a century ago. Brown said that if we had to deal with COVID-19 with the medical care of 1918, the death toll would probably be similar.

As time went on, the Spanish Flu somehow disappeared, but not before killing tens of millions of people globally. There is some belief that the virus mutated to the point of becoming less deadly, though it is not officially known how it went away.

Though Brown’s research is not complete, he has concluded that many of the reactions and rationales of the public against measures imposed to curb the spread of the Spanish Flu can be seen almost verbatim in the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. The resistance to masks and business closures, and the insistence that the virus is not that bad is almost echoed between both pandemics.